In 2015, I settled in on the Springfield, Massachusetts, headquarters of Merriam-Webster, America’s most storied dictionary firm. My challenge was to doc the bold reinvention of a traditional, and I hoped to get some definitions of my very own into the lexicon alongside the way in which. (A favourite early drafting effort, which I couldn’t consider wasn’t already included, was dogpile : “a celebration by which individuals dive on high of one another instantly after a victory.”) Merriam-Webster’s overhaul of its signature work, Webster’s Third New Worldwide Dictionary, Unabridged—a 465,000-word, 2,700-page, 13.5-pound doorstop printed in 1961 and by no means earlier than up to date—was already in full swing. The revision, which might be not a hardback ebook however an online-only version, requiring a subscription, was anticipated to take a long time.

Not lengthy after my arrival, although, every part modified. Web page views had been declining for Merriam-Webster.com, the corporate’s free, ad-driven income engine: Tweaks to Google’s algorithms had punished Merriam’s search outcomes. The corporate had all the time been lean and worthwhile, however the monetary hit was actual. Merriam’s mother or father, Encyclopedia Britannica, was dealing with challenges of its personal—who wanted an encyclopedia in a Wikipedia world?—and ordered cuts. Merriam laid off greater than a dozen staffers. Its longtime writer, John Morse, was compelled into early retirement. The revision of Merriam’s unabridged masterpiece was deserted.

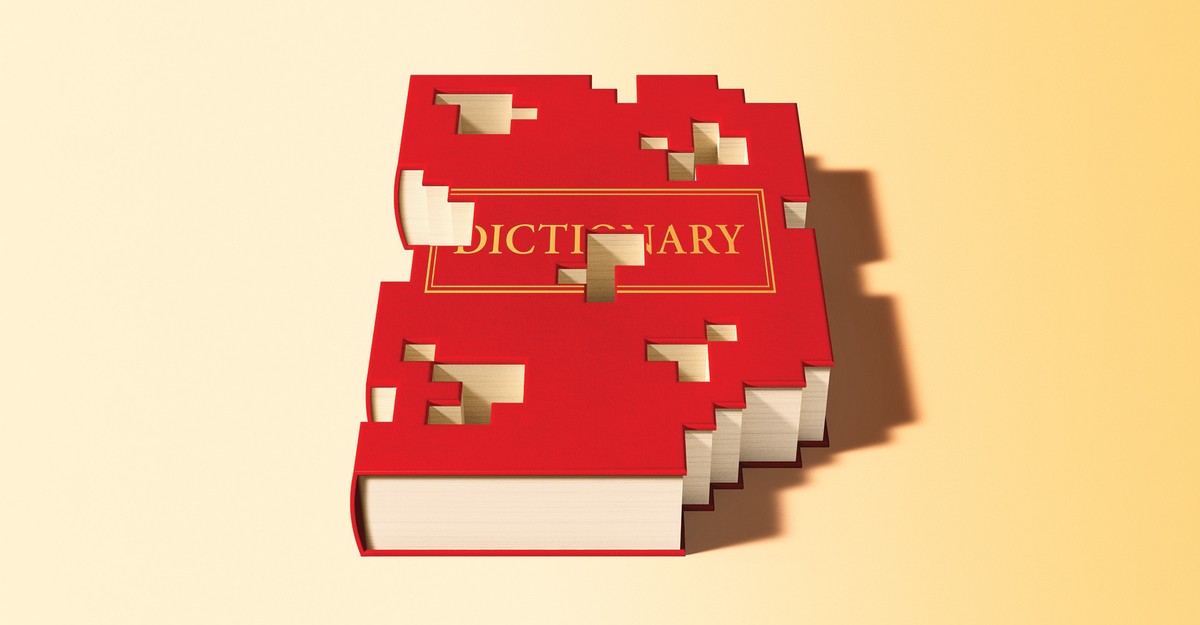

Name it the paradox of the trendy dictionary. We’re in a golden age for the examine and appreciation of phrases—a time of “meta consciousness” of language, as one lexicographer put it to me. Dictionaries are extra accessible than ever, accessible in your laptop computer or cellphone. Extra individuals use them than ever, and dictionary publishers now possess the digital wherewithal to intently observe that use. Podcasts, newsletters, and Phrases of the 12 months have popularized neologisms, etymologies, and utilization developments. In the meantime, analytical software program has revolutionized linguistic inquiry, enabling better understanding of the methods language works—when, how, and why phrases get away; the particular contexts for expressions and idioms. And all of that was true lengthy earlier than the rise of AI.

However these advances are additionally strangling the enterprise of the dictionary. Definitions, skilled and beginner, are a click on away, and most of the people don’t care or can’t inform whether or not what pops up in a search is skilled analysis, crowdsourced jottings, scraped knowledge, or zombie web sites. Earlier than he left Merriam, Morse informed me that legacy dictionaries face the identical rising well-liked mistrust of conventional authorities that media and authorities have encountered.

Different large names in American lexicography had been already receding. In 2001, a decade after releasing an version dubbed the “politically right dictionary” for its inclusion of womyn, herstory, waitron, and extra, Random Home deserted dictionary making altogether. Webster’s New World Dictionary cycled via company house owners till its final version, in 2014. The American Heritage Dictionary, printed in 1969 to problem Merriam’s Third, is an sometimes up to date shell of its legendary self.

By the beginning of this decade, the once-competitive American dictionary enterprise was basically down to 2 gamers: Merriam-Webster, with its 200 years of custom and model recognition, and Dictionary.com, whose founders, 30 years in the past, beat Merriam to the URL by just a few weeks. After it was acquired in 2008 by the media and web large IAC, Dictionary.com’s small editorial employees had innovated. After I visited its places of work in 2016, the corporate’s verticals for slang, emoji, memes, and phrases associated to gender and sexuality had been sturdy, and its periodic dictionary updates had been fashionable and substantial—a batch of entries included superfood and clicktivism. The corporate reportedly had greater than 5 billion annual searches within the mid-2010s, and in 2018 was among the many web’s 500 most-visited web sites.

In 2018, Dictionary.com was bought by the mortgage-industry titan (and Cleveland Cavaliers proprietor) Dan Gilbert’s firm Rock Holdings—apparently simply because Gilbert was a fan of dictionaries. He took a private curiosity within the challenge, and for just a few years, it appeared just like the digital way forward for the lexicon was at hand. The road inside the corporate was that Gilbert wished “to personal the English language.” And he did appear genuinely within the work of the dictionary. “Once in a while he would ask a query {that a} reader would possibly ask,” John Kelly, a longtime Dictionary.com editor, informed me. As an example, Gilbert was into excessive climate, Kelly stated, and had subordinates transient him on phrases reminiscent of bombogenesis. When Rock Holdings’ mortgage and monetary firms went public in 2020, Dictionary.com remained privately held, shielding the location from shareholder pressures.

In 2023, Dictionary.com employed three full-time veteran lexicographers—together with Grant Barrett, a co-host of the public-radio present A Manner With Phrases, and Kory Stamper, a former longtime Merriam-Webster editor and the creator of the memoir Phrase by Phrase—to bolster a crew of a couple of dozen freelancers. The purpose was to modernize the dictionary, which was a big enterprise. Dictionary.com was primarily based totally on The Random Home Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language (printed in 1966, up to date in 1987), which was primarily based on The New Century Dictionary (printed in 1927), which was primarily based on The Century Dictionary (printed in 1889), which was primarily based on The Imperial Dictionary of the English Language (printed in 1847). A few of the entries had been greater than 100 years previous.

The lexicography crew revised often considered phrases reminiscent of idea and speculation, which generate a number of visitors at the beginning of the college 12 months. It enhanced entries with new pronunciations, etymologies, and various senses, reminiscent of a brand new adjectival use of mid (“mediocre, unimpressive, or disappointing”). It eliminated sexist and archaic language and diversified names in instance sentences. (“ ‘John went to high school,’ ” Barrett informed me. “Why not Juan or Juanita or Giannis? This can be a multicultural society.”)

Barrett designed a studying program to assist flag rising lexical objects and turbocharge additions, tripling the amount of recent phrases added within the website’s periodic updates over the course of a 12 months. A February 2024 rollout included Barbiecore, mattress rotting, gradual vogue, vary nervousness, and enshittification, which the American Dialect Society had chosen a month earlier as its 2023 Phrase of the 12 months. (Of these phrases, solely enshittification has since been added by Merriam, and solely to a brand new slang portal, not the official dictionary.) The lexicography crew was revising a database to extra rapidly replace entries and publish them on social media, and creating a synonym-based recreation. It was coaching new lexicographers.

Dictionary.com couldn’t match Merriam’s historical past or repute. As a substitute, the corporate was making an attempt to place itself to “seize language on the tempo of change,” to be “hipper and extra experimental, but additionally rigorous AF,” Kelly stated. (Dictionary.com added the slang initialism for as fuck ; Merriam nonetheless has not.)

The piecemeal efforts improved the dictionary’s high quality and funky quotient. Barrett additionally liked the work: He was surrounded by colleagues who cared about language and the way it was offered, verbally and visually. For a time, Barrett may plug his fingers in his ears and tune out the sobering actuality: Though he and his colleagues had been getting paid properly, “the dictionary enterprise was crumbling,” he stated. “So experience it ’til the wheels fall off. And the wheels fell off.”

Not lengthy after Rock Holdings took over, the {industry} grew tougher. Google’s “information packing containers” had been hogging the highest of search pages with definitions licensed from the British dictionary writer Oxford, together with synonyms, antonyms, and, finally and predictably, AI-generated summaries of phrases’ meanings. The proprietary litter pushed down traditional-dictionary hyperlinks, and Dictionary .com’s visitors fell by about 40 %. On the similar time, the pandemic drained promoting income. The positioning tried to stanch the decline with extra advertisements, solely to create a worse person expertise.

Dictionary.com rolled out a Okay–12 on-line tutoring service, AI writing software program, and different schooling merchandise. None of it aligned with a dictionary’s mission, and none of it labored, staffers stated. Then, as rates of interest rose, income at Gilbert’s core mortgage enterprise plunged, leading to almost $400 million in losses. Even for a billionaire who was within the comparatively low-budget dictionary enterprise much less for revenue than for enjoyable, the underside line mattered, and the stress to generate income and reduce prices was inescapable.

In April 2024, Rock Holdings introduced that it had offered Dictionary.com to IXL Studying, the proprietor of Rosetta Stone, Vocabulary.com, and different on-line ed-tech manufacturers. Inside a month, IXL laid off the entire dictionary’s full-time lexicographers and dumped most of its freelancers. Together with non-lexicography employees, Dictionary.com had began 2024 with about 80 staff. After the sale, solely a handful remained. (A consultant for IXL stated that the corporate retained a number of the freelancers, introduced in its personal lexicographers, and now has a employees bigger than it was on the time of the acquisition.)

When he misplaced his job, Barrett wasn’t bitter, or stunned. Dictionary.com hadn’t aspired to have a full employees within the custom of the books on which it was primarily based, he stated. It didn’t have Merriam’s advertiser base, print backlist, or historic mission to protect, shield, and outline American English. Barrett understood its extra circumscribed challenge. “Dictionary content material is pricey,” Barrett stated. “Simply the price of lexicographers—individuals are costly, and the output is low. It is extremely troublesome to justify that only for the sake of completism. You’ll by no means have sufficient employees to maintain up. Individuals are too productive within the creation of language.”

It’s exhausting to know what future enterprise mannequin would possibly save the {industry}. Getting swallowed by a tech large anticipating hockey-stick progress has proved untenable. A billionaire keen to let the dictionary simply be the dictionary—a self-sustaining firm with a modest employees performing an outsize cultural job that may not all the time be worthwhile—seems to be much less doubtless after Dan Gilbert’s foray. A grand nationwide dictionary challenge—some collaboration amongst authorities, personal, nonprofit, and educational establishments—feels just like the Platonic excellent. However with universities and mental inquiry underneath assault in 2025, I’m not holding my breath.

At Merriam-Webster, the usual capitalist mannequin is working, no less than for now, as is its hybrid print-digital strategy. The writer has rebounded from its mid-2010s struggles. It was a social-media darling in the course of the first Trump administration, racking up likes and retweets for its smart-alecky and politically subversive social-media persona. (When Donald Trump tweeted “unpresidented” as a substitute of “unprecedented,” the Merriam account responded: “Good morning! The #WordOfTheDay is … not ‘unpresidented’. We don’t enter that phrase. That’s a brand new one.”) Britannica invested in software program, {hardware}, and people to allow Merriam to higher navigate Google’s algorithms. Merriam added a phalanx of video games, together with Wordle knockoffs and a dictionary-based crossword, to draw and retain guests.

Merriam has outlasted a protracted line of American dictionaries. However loads of family media names have been humbled by the shifting habits of digital customers. Even earlier than Google’s AI Overview started taking clicks from definitions written by flesh-and-bone lexicographers, the trajectory of the {industry} was clear.

After Merriam shut down its on-line unabridged revision, I caught across the firm’s 85-year-old brick headquarters, reporting and defining. I ultimately drafted about 90 definitions. Most of them didn’t make the reduce. However a handful are enshrined on-line, together with politically charged phrases reminiscent of microaggression and alt-right, and kooky ones reminiscent of sheeple and, sure, dogpile.

Whereas I’m pleased with these small contributions to lexicography, my wanderings via dictionary tradition satisfied me of one thing much more essential: the pressing want to avoid wasting this slowly fading enterprise. Twenty years in the past, an estimated 200 full-time business lexicographers had been working in america; immediately the quantity might be lower than 1 / 4 of that. At a time when contentious phrases dominate our conversations—assume revolt and fascism and pretend information and woke—the necessity for dictionaries to chronicle and clarify language, and function its watchdog, has by no means been better.

This text was tailored from Stefan Fatsis’s new ebook, Unabridged: The Thrill of (And Risk to) the Fashionable Dictionary. It seems within the October 2025 print version with the headline “Whither the Dictionary?”

While you purchase a ebook utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.