Books about masters and servants have a tendency to return with an inborn flaw: They’re written largely by these from the moneyed class, people who’ve seen the poor from above and should now, of their writing, illuminate their lives from inside. This hole can generally be breached by means of immersive journalism of the type championed by George Orwell in Down and Out in Paris and London or Barbara Ehrenreich in Nickel and Dimed. However such cases are uncommon, and even tougher to realize in international locations like India or Pakistan—locations with giant domestic-worker populations the place socioeconomic variations are so harshly inscribed that one can, as a rule, instantly infer an individual’s standing from their mannerisms and language.

That is what makes the work of the Pakistani American author Daniyal Mueenuddin so particular and stunning. Mueenuddin is a U.S.-educated descendant of a Pakistani feudal household; he spent years working an property in rural Punjab. In his prize-winning fiction, although, he’s by some means capable of enter the lives of the servant class with the identical gentleness and a focus that he lavishes on the ultrarich. The issues of drivers, retainers, maids, and cooks exist alongside the romantic issues of Paris-hopping Pakistanis with cocaine addictions in his justly acclaimed debut assortment, In Different Rooms, Different Wonders, from 2009. Small particulars shine. Studying about, say, the household lifetime of Nawabdin, an electrician “who flourished on a signature skill, a method for dishonest the electrical firm by slowing down the revolutions of electrical meters,” one wonders: How does he know a lot? How does he re-create the lives of these immured inside a feudal system with out reinforcing his personal place by means of condescending, morose social realism?

Mueenuddin has cited the creator Ivan Turgenev—himself an property proprietor who captured the lives of each serfs and aristocrats in Nineteenth-century Russia—as certainly one of his inspirations. Turgenev, hampered by czarist censorship, didn’t write polemics about struggling serfs however as an alternative created hyperrealist, idiosyncratic slices of life that might later encourage Ernest Hemingway. Turgenev’s tales, particularly his 1852 assortment, A Sportsman’s Pocket book, not directly led to the tip of serfdom by humanizing the peasantry for Czar Alexander II. Briefly, Turgenev was the uncommon property proprietor who listened.

Mueenuddin does the identical in his newest work, This Is The place the Serpent Lives. His first e book in 17 years and his debut novel, it’s a feast of sustained noticing, regardless of an overarching flaw. One of many major strands in Serpent is predicated, in response to an interview with The New Yorker, on the lifetime of a swashbuckling driver employed for years by Mueenuddin’s father. His fictional driver, Yazid, is the ethical heart of the novel, described as “an ambling bear” with enormous sideburns “transferring to his personal North.” As a younger orphan, Yazid was a cook dinner’s apprentice who emulated the wealthy schoolboys he served, desiring to slowly insinuate himself into their class—solely to be thwarted by a jealous, older maidservant.

Mueenuddin’s novel basically includes 4 novella-like storylines about grand landowning households and their workers in Pakistan from the Nineteen Fifties to the current. In addition to Yazid’s story, two brief narratives observe reluctant feudal potentates. A closing story, which takes up the vast majority of the novel, focuses on Yazid’s a lot youthful protégé, Saqib, a servant boy of “wonderful sensibility and intelligence” who additionally seeks to affix the higher class.

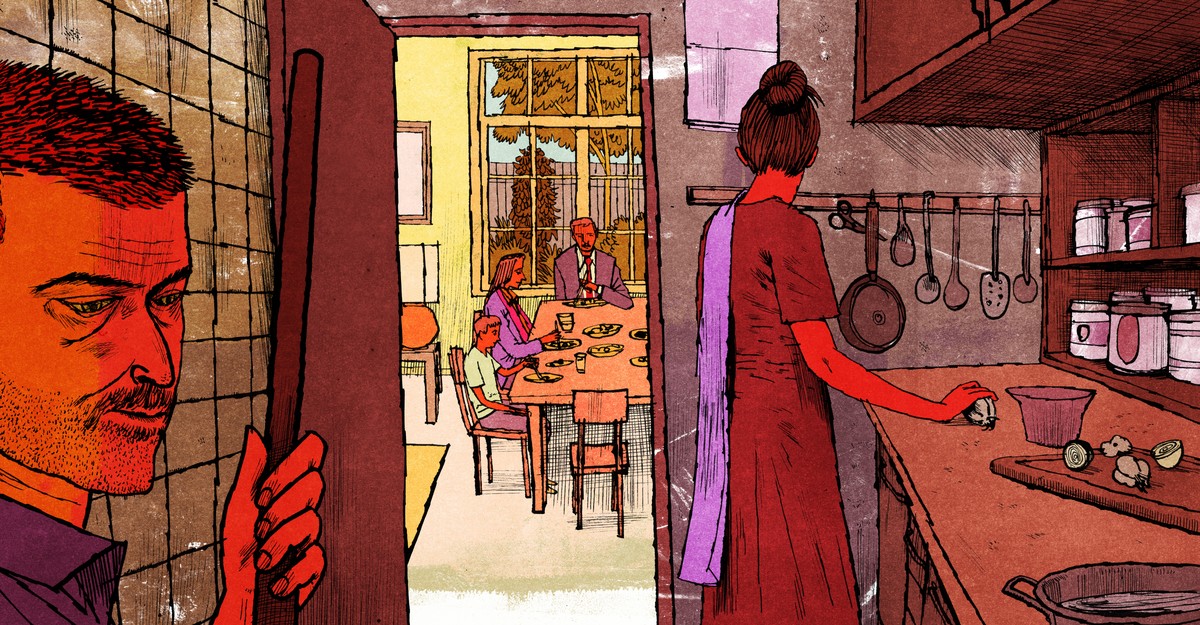

Mueenuddin’s novel means that there are ethical prices to each the wealthy and the poor for residing in a system that enables such little mobility. Rich characters verge on making reforms, then pull again on the slightest complication. Within the course of, they continue to be caught inside their “ordered purposeless” lives, as Mueenuddin wrote in his assortment. The servants, in the meantime, who’re “extra fed than paid,” acknowledge that solely probably the most brazen dishonest and corruption can break them out of their squalid circumstances—the kind of corruption, after all, that has enabled the elite to thrive in a rustic the place significant land reform by no means occurred and historical inequalities persist. A novelist depicting each these lessons should discover a sublime approach to combine tales of inherited ennui and determined striving. If Mueeneddin doesn’t solely succeed, that is partially as a result of the unyielding feudal order of Pakistan implies that the lives of servants and masters hardly ever intersect in significant methods.

Saqib’s story captures the dilemma of the aspirant much more fiercely than Yazid’s does. “Respectful however not servile,” Saqib enters the great graces of his mistress, Shahnaz Atar, an clever girl who, “like most Lahori girls of her class,” Mueenuddin writes, “battled consistently to search out and practice and preserve family servants.” Saqib is entrusted with increasingly duty as he grows up, finally organising an formidable cucumber-farming scheme on the Atars’ property in rural Punjab. He figures that it’s going to take one cautious, main act of corruption to lastly ascend to the elite: “Every unfaithful mark that he inscribed” within the account books can be, Mueenuddin writes, “one other step in his emancipation.” Alas, it’s this alternative that will get him into bother and causes the wonderful internet of relationships round him to crumble, throwing him violently again to his origins because the mere son of a gardener.

As in his story assortment, Mueenuddin succeeds right here in portray Yazid and Saqib and a number of secondary characters on the social ladder as distinct people, right down to their faces and habits and household lives. He additionally reveals how, at this late stage of historical past—wherein Chinese language smartphones, Western porn, and Fb “confettied throughout” the populace—the gamers are extra conscious than ever of their explicit roles. Shahnaz, who grew up largely overseas, sees her place as mistress of an property “by means of the lens of her Western politics and expertise,” even finding out the Russians, together with Turgenev, to grasp the advanced social dynamics unfolding on her farm. Her husband’s cousin Rustom, who returns from America to take over his household’s land after his dad and mom and grandfather die, finds himself tacitly okaying the beating of a employee from a rival property. “What occurred to school days and marching for justice in South Africa and in solidarity with ship staff in Poland?” he wonders. In the meantime, Saqib fastidiously observes the conduct of his masters, the Atars, to be able to mannequin it—noting, for instance, that they deal with “consuming as ceremony.”

What offers Mueenuddin a tougher time is discovering a construction that generates which means from the interaction between the higher and the decrease lessons. His 4 tales observe no clear arc, flitting from one time interval or character to a different. In a short-story assortment resembling Different Rooms, the query of a story by means of line doesn’t come up. You get discrete tales (or rooms!) about folks from totally different lessons, and the hyperlinks between characters are delicate. In Serpent, nevertheless, Mueenuddin’s makes an attempt to offer the lives of Yazid and Saqib the identical weight as these of the property house owners is unusually lopsided; his characters’ connections really feel extra circumstantial than inherent to the narrative. A 150-page novel about Saqib alone, for instance, may need succeeded greater than this good however blowsy e book, which had me writing, at web page 100, “I nonetheless don’t know what that is about.”

Alas, this pitfall has as a lot to do with the construction of Pakistani society because it does with the construction of the e book. Though masters and servants occupy the identical areas, their lives don’t apply equal strain on one another. A servant may have a tumultuous internal life, however until he commits a significant crime (as in, for example, Aravind Adiga’s Booker-winning The White Tiger), his feelings are unlikely to contaminate the grasp. The grasp, in flip, often lives in one other sphere—certainly one of extramarital affairs and boozy events and corrupt enterprise offers. Shahnaz, for instance, merely turns away bitterly and sadly after Saqib’s crime. One needs Mueenuddin had devised a story wherein she skilled a deeper, extra difficult fallout—an exception to the rule.

And so lives which can be disparate proceed to really feel wrenched aside. What we have now right here shouldn’t be a novel in any respect however one other linked short-story assortment—if solely Mueenuddin had named it as such! The lives of those characters are of excellent curiosity. It’s the kind wherein they stay that’s flawed.

If you purchase a e book utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.