The Civil Struggle isn’t what it was. As a substitute of the romantic model, a “good conflict” of braveness and glory, that emerged within the battle’s instant aftermath, or the post-civil-rights-era emphasis on the conflict because the vector of liberation for 4 million enslaved African Individuals, a newer route has been labeled the “darkish flip.” Grim relatively than celebratory, it has chronicled the conflict’s price and cruelty, exploring topics comparable to dying, ruins, hunger, illness, atrocities, torture, amputations, and postwar trauma, in addition to a freedom that was quickly undermined.

W. Fitzhugh Brundage’s gripping new ebook, aptly titled A Destiny Worse Than Hell: American Prisoners of the Civil Struggle, represents a necessary contribution to this rethinking in its account of what was maybe essentially the most horrifying realization of the struggling and inhumanity the conflict produced. However Brundage, who teaches on the College of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, does greater than increase our understanding of a uncared for facet of Civil Struggle historical past. His examine affords a window into bigger questions—in regards to the evolution of legal guidelines of conflict and the definition of conflict crimes, in regards to the moral duty of combatants, in regards to the progress of the nation-state and its attendant paperwork, and in regards to the defining presence of race within the morality play of American historical past. As one Vermont infantryman wrote from a Accomplice jail camp, “Right here is the place I can see human nature in its true mild.”

At first of the preventing, in 1861, nobody anticipated that greater than 400,000 males would change into prisoners of conflict and that at the least half of those would spend prolonged time in websites of what we might now name mass incarceration. The chances of being captured by the enemy in World Struggle II have been 1 in 100. Within the Civil Struggle, they have been 1 in 5. As Brundage observes, thrice as many Union troopers died on the Accomplice camp in Andersonville, Georgia, as at Gettysburg. General, roughly 10 p.c of the conflict’s deaths occurred in prisons.

However jail camps attained this scale and significance solely steadily. Each side have been initially unsure about how one can deal with enemy captives. “What ought to be executed with the prisoners?” the Richmond Whig requested. Remedy was largely advert hoc and depended to a substantial diploma on particular person commanders, however usually prisoners can be exchanged or positioned on parole—granted their freedom however required by oath to not return to navy motion. Rooted in assumptions about gents’s honor and the integrity of pledges, the notion of parole now appears quaint, and it disappeared because the brutality of the conflict escalated. Some members of Abraham Lincoln’s Cupboard even argued for executing Accomplice prisoners as traitors, however Congress and the general public exerted strain on the president to ascertain procedures to facilitate the return of captured Yankees. Formal provisions for the trade of prisoners was not agreed upon till the summer season of 1862, delayed by the Union’s reluctance to take any motion that implied recognition of Accomplice nationhood. Beneath the phrases of the Dix-Hill settlement, some 30,000 prisoners have been returned from captivity by the autumn, however the formal trade association was quickly upended.

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued in preliminary type in September 1862, supplied for the recruitment of Black troops into the Union Military. Viewing this new coverage as equal to fomenting slave rebel, the South rejected any trade of Black troopers and didn’t lengthen them the protections of prisoners of conflict. They may be killed on the battlefield even after they surrendered, or remanded into slavery, or consigned to camps the place they endured disproportionately harsh therapy.

Lincoln was firm in his resistance to those measures. If Black troopers couldn’t be exchanged, no troopers can be exchanged. The Dix-Hill settlement was suspended, and the variety of prisoners of conflict grew exponentially; the end result was camps the dimensions of cities and untold distress for hundreds of males in each the North and the South. Solely over the past months of the conflict, with slavery disintegrating and northern victory all however assured, did exchanges resume.

Brundage characterizes the creation of the camps as an “innovation,” describing them as “experiments in custodial imprisonment” that exceeded anybody’s prewar creativeness. These have been fashionable innovations made potential by the introduction of railroads to move prisoners lengthy distances from battlefields, and by the expansion of administrative and organizational buildings required to handle not simply mass armies however a whole lot of hundreds of prisoners. Though they emerged out of war-born imperatives, the camps have been, he insists, a alternative made by northern and southern coverage makers alike, motivated by assumptions and functions for which Brundage argues they have to bear duty.

Each side believed that any sympathetic act towards the enemy would signify an insult to their very own troopers. The Union commissary normal accountable for jail administration proclaimed that “it isn’t anticipated that something extra might be executed to supply for the welfare of the insurgent prisoners than is completely needed,” and that work on a jail camp underneath renovation ought to “fall far wanting perfection.” Throughout spring and summer season months, he mandated that any clothes distributions embody neither underwear nor socks.

However regardless of the ethical and logistical shortcomings evident on each side, Brundage attracts a transparent distinction between North and South. “By any affordable measure,” he judges, “Accomplice prisoners have been higher saved than their Union counterparts.” Southern officers, he concludes, “by no means totally accepted the duty to supply for prisoners of conflict.” Union prisoners have been regarded not as human beings however as “a safety legal responsibility that imposed no moral crucial.” The South housed its captives in ill-adapted current areas. Richmond’s Libby Jail was a transformed tobacco manufacturing facility; the Salisbury, North Carolina, jail had been a textile mill; camps in Montgomery and Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and Macon, Georgia, have been former slave jails. On the infamous Andersonville camp, no buildings have been supplied in any respect. Males weren’t even issued tents however scrounged to obtain shirts, blankets, or different bits of material to drape over sticks of wooden to create what they known as “shebangs.” These unable to seek out material or wooden dug holes within the floor.

The Union, in distinction, erected barracks and designed purpose-built enclosures for this new experiment in large-scale imprisonment. These overseeing Union jail camps acknowledged that offering meals and shelter for captives was certainly an ethical obligation, even when on quite a few events they didn’t ship adequately on that dedication. But the 25 p.c dying charge on the North’s worst jail, in Elmira, New York, got here near that at Andersonville (29 p.c); general, the mortality charge was 16 p.c for Union prisoners and 12 p.c for Confederates. Cruelty and corruption acknowledged no regional boundaries, and officers on each side appear to have come nearer to despising than sympathizing with their struggling captives.

There’s a protracted custom—born within the midst of the conflict itself—of accusation and debate about which aspect behaved worse. Defending the South’s therapy of its prisoners turned a central theme for the neo-Confederates of the Misplaced Trigger because the motion to rehabilitate the South emerged within the late nineteenth century. The blame for the surge in incarceration in 1863 and past ought to relaxation with the Union, they contended, for it was the North that halted the prisoner trade. Urgent the benefit of their superior numbers, the North mercilessly saved captured Confederates in jail camps to forestall them from returning to the sector to replenish the South’s diminishing ranks. The North’s selections about prisoner exchanges have been primarily based on navy calculations, not benevolent concern for Black captives. The South, they argued, did its finest with its prisoners, given the scarcities of assets obtainable to Accomplice troopers and residents alike, scarcities they blamed on the Union effort to destroy the southern economic system by blockading ports.

Skilled historians within the early twentieth century weren’t as explicitly partisan because the United Daughters of the Confederacy and their supporters. But, influenced by William B. Hesseltine’s field-defining Civil Struggle Prisons, revealed in 1930, they adopted a sort of everybody-inevitably-made-mistakes strategy that exonerated Confederates of any intentional ethical failings. On the identical time, they attributed to the North a vindictiveness arising from “abolitionist propaganda” that exaggerated Accomplice jail atrocities.

The primary complete—one would possibly say encyclopedic—examine of jail camps since Hesseltine, Brundage’s ebook challenges these arguments head-on and assigns duty to the South’s unwavering dedication to slavery and Black subordination. Submit-civil-rights-era attitudes in regards to the equality of African Individuals have prompted a unique evaluation of who prompted the breakdown in prisoner exchanges, and thus bore the onus for the struggling and dying that ensued: It was the South’s refusal to acknowledge Black troopers as free males and thus deal with them as prisoners of conflict, not Lincoln’s principled response to this Accomplice coverage, that produced such massive numbers of Civil Struggle captives. And Brundage ensures that his readers is not going to dismiss the report of jail atrocities. Though he affords examples of miseries from each northern and southern camps, his portrait of Andersonville leaves essentially the most vivid impression of what the conflict’s ethical compromises got here to imply.

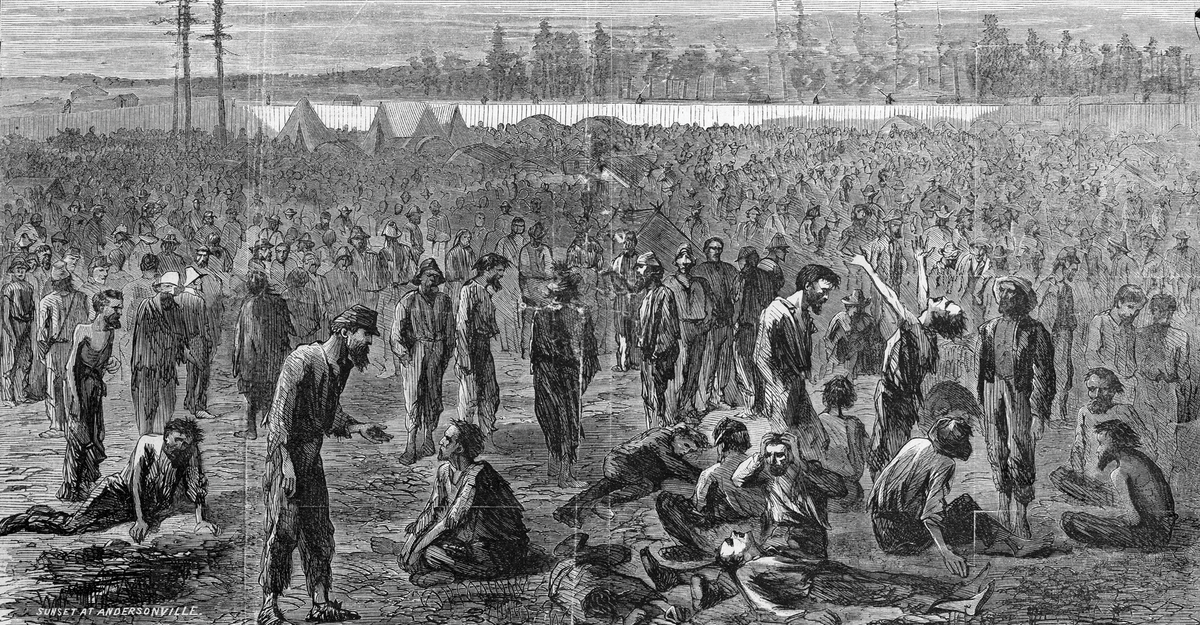

Andersonville was not created till February 1864, however within the months that adopted, as many as 90 trainloads, containing 75 males to a boxcar, quickly established its unprecedented scale. The camp consisted of a stockade erected round a 16-acre subject by 200 enslaved employees commandeered from close by plantations. Andersonville was designed to carry 10,000 prisoners, however its inhabitants reached as excessive as 33,000. The camp had no sanitation system, no barracks, no clothes allocations, and scant rations distributed raw to males with out pans or utensils or firewood. Illness—scurvy, typhoid, dysentery—was rampant amongst prisoners, however medical therapy was worse than insufficient. Within the jail hospital, made up of dilapidated tents, 70 p.c of the sufferers died. When Accomplice officers arrived to examine the camp in Might 1864 and once more that August, they have been shocked by what they noticed. Almost 13,000 males lie buried within the Andersonville Nationwide Cemetery, which the nurse and future founding father of the American Purple Cross Clara Barton helped set up on the positioning on the finish of the conflict.

A fantastic energy of Brundage’s examine is the breadth and depth of his analysis; he makes deft use of all kinds of proof past the official information on which a lot earlier historic work on Civil Struggle prisons has rested. He opens the ebook with a consideration of a sequence of images of Andersonville that in themselves make minimizing the horror and struggling not possible. A photographer from Macon, 60 miles away, seemingly compelled by pure curiosity, spent an August day in 1864 taking panoramic photos of life throughout the camp stockade—the bottom obscured underneath a sea of shabby improvised shelters; the swarm of prisoners gathered to obtain rations; the lads seated bare-bottomed over an open trench that will carry their waste into the identical stream that supplied their ingesting water. Illustrations all through the ebook assist Brundage’s insights and arguments.

But maybe much more hanging than the images are the phrases taken from prisoners’ letters, diaries, and memoirs. Brundage accompanies his narrative of evolving jail insurance policies with voices and tales of particular person males. “Are we to be exchanged, or are we to be left right here to perish?” requested Orin H. Brown, William H. Johnson, and William Wilson, three Black Union sailors, in the summertime of 1863, nonetheless packed right into a crowded Charleston jail half a 12 months after their ship had surrendered and their captured comrades, all of them white, had been exchanged. By some means their petition—miraculously evading Accomplice interception and touring, by way of the Bahamas, to Washington—arrived on the Navy secretary’s desk, although they seemingly weren’t launched till the top of the conflict. For Frederic Augustus James, a prisoner at Salisbury, unreliable mail was one in all many sources of agony; he discovered of his 8-year-old daughter’s dying 5 months after the actual fact, a succession of his spouse’s letters having by no means reached him. 4 months after his switch to Andersonville, he died of dysentery.

William Hesseltine and his followers had dismissed such sources as at finest partial and at worst partisan of their exposition of the cruelties inflicted by their wartime enemies. Brundage approaches these supplies with an appropriately crucial eye, demonstrating their consistency with different information and their worth in offering deeper human perception into prisoners’ experiences. What Hesseltine claimed as goal historical past, Brundage each tells and reveals us, was if truth be told removed from goal; it positioned the story within the palms of the official report keepers whereas silencing those that have been the victims of their selections and insurance policies. Incorporating their accounts, Brundage offers his readers with a far richer and extra full model of the previous.

On the identical time, he casts his ebook as being in regards to the current and the long run as nicely. Mass internment, as he portrays it, is a product of modernity, made potential by expertise and rising organizational and logistical capacities. Nevertheless it was additionally a deliberate alternative, a callous and acutely aware choice. “What mixture of institutional authority and procedures,” he asks, “eroded the ethical inhibitions of officers, commanders, and camp workers, thereby making it simpler for them to desert the duty they may in any other case have felt to ease the struggling of the man people” at Andersonville? It’s exhausting to have a look at essentially the most horrible photos of captives finally returned to the North with out seeing in a single’s thoughts the images of these liberated from Nazi focus camps eight a long time later.

But the calls for of modernity produced some humane outcomes that additionally presaged the long run. The dilemma of how one can take care of Civil Struggle prisoners served as a catalyst for Basic Orders No. 100, issued by the Struggle Division in 1863. It was the first systematic codification of the principles of conflict and have become the muse for contemporary worldwide humanitarian legislation. It led to the trial and subsequent execution on the conflict’s finish of Henry Wirz, the commander at Andersonville, for conspiring “to impair the lives of Union prisoners.” Northern prosecutors had hoped to cost high Accomplice management, together with President Jefferson Davis, in a sequence of postwar trials. Ultimately, Wirz was their solely main conviction, as a result of southern outrage and northern calls for to forgive and overlook introduced an finish to the authorized effort. However Wirz’s trial represented the origin of recent prosecution of conflict crimes.

“Navy necessity,” Basic Orders No. 100 directs, “doesn’t admit of cruelty.” Within the Civil Struggle’s jail camps, it did simply that. But the assertion encodes an aspiration and an expectation, if not all the time an enforceable legislation. Born of Civil Struggle struggling, worldwide humanitarian legislation calls for, as does Brundage’s vital ebook, that we acknowledge cruelty as a alternative.

This text seems within the March 2026 print version with the headline “Deadlier Than Gettysburg.”

Once you purchase a ebook utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.