The story I’d heard was that Mick Jagger purchased his first Clifton Chenier file within the late Sixties, at a retailer in New York’s Greenwich Village. However after we talked this spring, Jagger instructed me he didn’t do his file purchasing within the Village. It will have been Colony Information in Midtown, he mentioned, “the most important file retailer in New York, and it had the very best choice.” Jagger was in his 20s, not far faraway from a suburban-London boyhood spent steeping within the American blues. I pictured him eagerly leafing via Chess Information LPs and J&M 45s till he got here throughout a chocolate-brown 12-inch file—Chenier’s 1967 album Bon Ton Roulet!

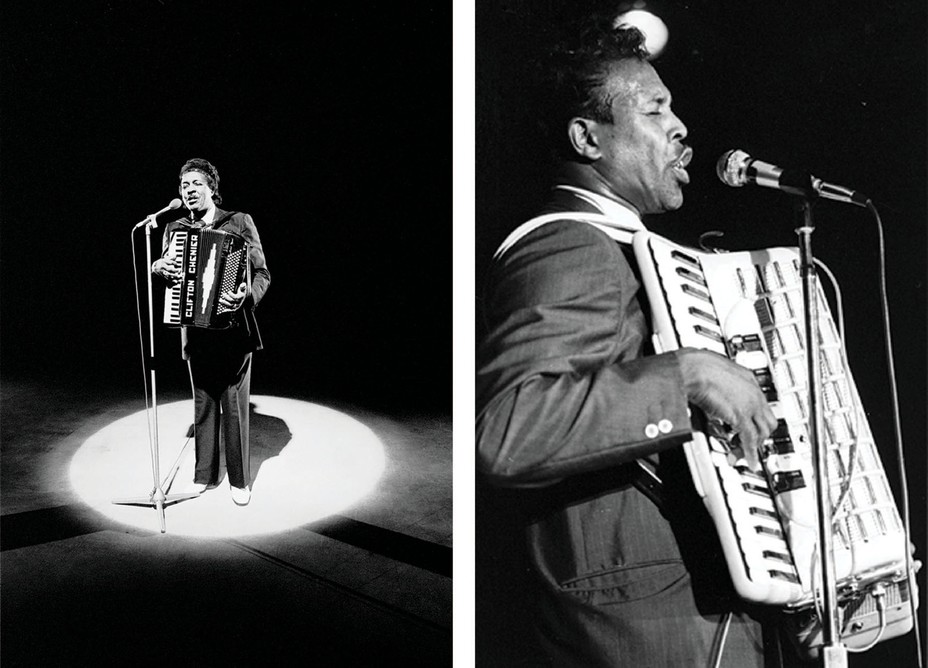

On the duvet, a younger Chenier holds a 25-pound accordion the size of his torso, an enormous, mischievous smile on his face. Bon Ton Roulet! is a basic zydeco album showcasing the Creole dance music of Southwest Louisiana, which blends conventional French music, Caribbean rhythms, and American R&B. This was completely different from the Delta and Chicago blues that Jagger and his Rolling Stones bandmates had grown up with and emulated on their very own information. Though typically taking the type of slower French waltzes, zydeco is extra up-tempo—it’s social gathering music—and options the accordion and the rubboard, a washboard hooked over the shoulders and hung throughout the physique like a vest. Till he found zydeco, Jagger recalled, “I’d by no means heard the accordion within the blues earlier than.”

Chenier was born in 1925 in Opelousas, Louisiana, the son of a sharecropper and accordion participant named Joseph Chenier, who taught his son the fundamentals of the instrument. Clifton’s older brother, Cleveland, performed the washboard and later the rubboard. Clifton had commissioned an early prototype of the rubboard within the Nineteen Forties from a metalworker in Port Arthur, Texas, the place he illustrated his imaginative and prescient by drawing the design within the grime, creating considered one of a handful of devices native to the US and perpetually altering the percussive sound of Creole music.

Inside a number of years, the brothers had been acting at impromptu home dances in Louisiana dwelling rooms. They’d start enjoying on the porch till a crowd assembled, then go inside, pushing furnishings towards the partitions to create a makeshift dance corridor. Ultimately, they labored their manner via the chitlin circuit, a community of venues for Black performers and audiences. They performed Louisiana dance halls the place the ceilings hung so low that Cleveland might push his left hand flat to the ceiling to stretch his again out with out ever breaking the rhythm of what he was enjoying together with his proper.

Influenced by rock-and-roll pioneers corresponding to Fat Domino, Chenier integrated new components into his music. As he instructed one interviewer, “I put a little bit rock into this French music.” With the assistance of Lightnin’ Hopkins, a cousin by marriage, Chenier signed a take care of Arhoolie Information. By the late ’60s, he and his band had been repeatedly enjoying excursions that stretched throughout the nation, regardless of the insistence from segregationist promoters that zydeco was a Black sound for Black audiences. He began enjoying church buildings and festivals on the East and West Coasts, the place individuals who’d by no means heard the phrase zydeco had been awestruck by Chenier: He’d typically arrive onstage in a cape and a velvet crown with cumbersome costume jewels set in its arches.

Chenier got here to be often known as the King of Zydeco. He toured Europe; gained a Grammy for his 1982 album, I’m Right here! ; carried out at Carnegie Corridor and in Ronald Reagan’s White Home; gained a Nationwide Heritage Fellowship from the Nationwide Endowment for the Arts. He died in 1987, at age 62.

This fall, the Smithsonian’s preservation-focused Folkways Recordings will launch the definitive assortment of Chenier’s work: a sprawling field set, 67 tracks in all. And in June, to mark the centennial of Chenier’s start, the Louisiana-based Valcour Information launched a compilation on which musicians who had been impressed by Chenier contributed covers of his songs. These embrace the blues artist Taj Mahal, the singer-songwriter Lucinda Williams, the people troubadour Steve Earle, and the rock band the Rolling Stones.

In 1978, Jagger met Chenier, due to a musician and visible artist named Richard Landry.

Landry grew up on a pecan farm in Cecilia, Louisiana, not removed from Opelousas. In 1969, he moved to New York and met Philip Glass, changing into a founding member of the Philip Glass Ensemble, wherein he performed saxophone. To pay the payments between performances, the 2 males additionally began a plumbing enterprise. Ultimately, the ensemble was reserving sufficient gigs that they gave up plumbing.

Landry additionally launched into a profitable visual-art profession, photographing contemporaries corresponding to Richard Serra and William S. Burroughs and premiering his work on the Leo Castelli Gallery. He nonetheless received again to Louisiana, although, and he’d sometimes sit in with Chenier and his band. (After Landry proved his chops the primary time they performed collectively, Chenier affectionately described him as “that white boy from Cecilia who can play the zydeco.”) Landry grew to become a type of cultural conduit—a hyperlink between the avant-garde scene of the North and the Cajun and Creole cultures of the South.

Landry is an previous good friend; we met greater than a decade in the past in New Orleans. Sitting in his residence in Lafayette lately, he instructed me the story of the evening he launched Jagger to Chenier. As Landry remembers it, he first met Jagger at a Los Angeles home social gathering following a Philip Glass Ensemble efficiency on the Whisky a Go Go. The following evening, as luck would have it, he noticed Jagger once more, this day trip at a restaurant, they usually received to speaking. In some unspecified time in the future within the dialog, “Jagger goes, ‘Your accent. The place are you from?’ I mentioned, ‘I’m from South Louisiana.’ He blurts out, ‘Clifton Chenier, the very best band I ever heard, and I’d like to listen to him once more.’ ”

“Dude, you’re in luck,” he instructed Jagger. Chenier was enjoying a present at a highschool in Watts the next evening.

Landry known as Chenier: “Cliff, I’m bringing Mick Jagger tomorrow evening.”

Chenier responded, “Who’s that?”

“He’s with the Rolling Stones,” Landry tried to elucidate.

“Oh yeah. That journal. They did an article on me.”

It appears the Rolling Stones had but to make an impression on Chenier, however his music had clearly influenced the band, and never simply Jagger. The earlier 12 months, Rolling Stone had printed a characteristic on the Stones’ guitarist Ronnie Wooden. In a single scene, Wooden and Keith Richards convene a 3 a.m. jam session on the New York studios of Atlantic Information. On gear borrowed from Bruce Springsteen, they play “Don’t You Misinform Me”—first the Chuck Berry model, then “Clifton Chenier’s Zydeco interpretation,” because the article described it.

Chenier was in Los Angeles enjoying what had develop into an annual present for the Creole group dwelling within the metropolis. The stage was set on the Verbum Dei Jesuit Excessive Faculty gymnasium, by the sting of the basketball court docket. Jagger was struck by the viewers. “They weren’t dressing as different folks of their age group,” he instructed me. “The style was utterly completely different. And naturally, the dancing was completely different than you’d usually see in an enormous metropolis.”

The band was already performing by the point he and Landry arrived. After they walked in, one girl squinted in Jagger’s course, pausing in a second of potential recognition, earlier than altering her thoughts and turning away.

Chenier was at middle stage, thick gold rings lining his fingers as they moved throughout the black and white keys of his accordion, his title embossed in daring block kind on its aspect. Cleveland stood beside him on the rubboard. Robert St. Julien was arrange within the again behind a three-piece drum package—only a bass drum, a snare, and a single cymbal, cracked from the opening within the middle out to the very edge.

Jagger took all of it in, watching the group dance a two-step and considering, “Oh God, I’m going to have to bounce. How am I going to do that dance that they’re all doing? ” he recalled. “However I managed in some way to faux it.”

At intermission, a cluster of followers, talking in excited bursts of Creole French, began shifting towards the stage, holding out papers to be autographed. Landry and Jagger had been standing close by. Jagger braced himself, assuming that among the followers may descend on him. However the crowd moved rapidly previous them, urgent towards Clifton and Cleveland Chenier.

Earlier than the evening was over, Jagger himself had the possibility to fulfill Clifton, however solely mentioned a fast hiya. “I simply didn’t wish to trouble him or something,” he instructed me. “And I used to be simply having fun with myself being one of many viewers.”

The following time Mick Jagger and Richard Landry crossed paths was Might 3, 2024: the day after the Rolling Stones carried out on the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Competition. Throughout their set, the Stones had requested the accordion participant Dwayne Dopsie, a son of one other zydeco artist, Rockin’ Dopsie, to accompany the band on “Let It Bleed.”

A meal was arrange at Antoine’s, within the French Quarter, by a mutual good friend, the musician and producer C. C. Adcock. Adcock had been engaged on plans for the Clifton Chenier centennial file for months and was nicely conscious of Jagger’s affection for zydeco. He waited till the meal was over, when everybody was saying their goodbyes, to say the venture to Jagger. “And with out hesitation,” Landry recalled, “Mick mentioned, ‘I wish to sing one thing.’ ”

As the ultimate addition to the album lineup, the Stones had been the final to decide on which of Chenier’s songs to file. Trying on the observe itemizing, Jagger observed that “Zydeco Sont Pas Salé” hadn’t been taken. “Isn’t that, like, the one?” Adcock remembers him saying. “The one the entire style is called after? If the Stones are gonna do one, shouldn’t we do the one ?”

The phrase zydeco is broadly believed to have originated within the French phrase les haricots sont pas salés, which interprets to “The snap beans aren’t salty.” Zydeco, in accordance with this principle, is a Creole French pronunciation of les haricots. (The lyrical fragment probably comes from juré, the call-and-response music of Louisiana that predates zydeco; it reveals up as early as 1934, on a recording of the singer Wilbur Shaw made in New Iberia, Louisiana.) Many interpretations of the phrase have been provided through the years. Essentially the most simple is that it’s a metaphorical manner of claiming “Occasions are robust.” When cash ran quick, folks couldn’t afford the salt meat that was historically cooked with snap beans to season them.

The Stones’ model of “Zydeco Sont Pas Salé” opens with St. Julien, Chenier’s longtime drummer, enjoying a backbeat with brushes. He’s 77 now, now not the younger man Jagger noticed in Watts in 1978. “I stop enjoying music about 10 years in the past, to inform the reality,” he mentioned after we spoke this spring, however you wouldn’t understand it by how he sounds on the observe. Keith Richards’s guitar half, guttural and revving, meets St. Julien within the intro and builds steadily. The melody is launched by the accordionist Steve Riley, of the Mamou Playboys, who instructed me he’d tried to “play it like Clifton—you recognize, free-form, simply from really feel.”

It’s unusual that it doesn’t really feel stranger when Jagger breaks into his vocal, sung in Creole French. His imitation of Chenier is without delay spot-on but unmistakably Jagger.

I requested him how he’d honed his French pronunciation. “I’ve truly tried to write down songs in Cajun French earlier than,” he mentioned. “However I’ve by no means actually gotten anyplace.” To get “Zydeco Sont Pas Salé” proper, he grew to become a pupil of the music. “You simply hearken to what’s been achieved earlier than you,” he instructed me. “See how they pronounce it, you recognize? I imply, yeah, in fact it’s completely different. And West Indian English is completely different from what they converse in London. I attempted to do a job and I attempted to do it in the best way it was historically achieved—it will sound a bit foolish in excellent French.”

Zydeco united musical traditions from across the globe to develop into a defining sound for one of the vital distinct cultures in America. Chenier, the accordionist within the velvet crown, then launched zydeco to the world, influencing artists throughout genres.

Once I requested Jagger why, at age 81, he had determined to make this recording, he mentioned, “I believe the music deserves to be identified and the music deserves to be heard.” If the music helps new listeners uncover Chenier—to have one thing just like the expertise Jagger had when he first dropped the needle on Bon Ton Roulet!—that might be a welcome outcome. However Jagger pressured that this wasn’t the first cause he’d lined “Zydeco Sont Pas Salé.” Singing to St. Julien’s beat, Jagger the rock star as soon as once more turns into Jagger the Clifton Chenier fan.

“My most important factor is simply that I personally prefer it. what I imply? That’s my attraction,” he mentioned. “I believe that I simply did this for the love of it, actually.”

This text seems within the July 2025 print version with the headline “When Mick Jagger Met the King of Zydeco.”